Our blood is a bountiful source of information that cancer researchers and clinicians have been tapping into for over a century. For instance, many cancer biomarkers (quantifiable indicators of cancer presence) can be found in blood and are useful in making clinical decisions [1]. It is important to note, though, that biomarkers aren’t only found in blood. For example, a CT scan or molecular profiling of a tissue biopsy may also act as cancer biomarkers [1,2].

One of the first cancer biomarkers I learned about was the prostate-specific antigen (PSA), when unfortunately, my father was diagnosed with prostate cancer. PSA is a protein secreted by the prostate, and in healthy men only small amounts circulate the bloodstream. When the PSA level in blood rises, it may indicate prostate cancer [3]. In my father’s case, testing for PSA allowed for early detection of his cancer and led to a successful treatment. However, PSA isn’t a perfect biomarker since it’s not specific to prostate cancer. For example, some men may have increased PSA levels due to an inflamed prostate or a urinary tract infection. Because of this, increased PSA levels aren’t enough to diagnose prostate cancer, so physicians must take a tissue biopsy of the prostate to investigate further [3].

Blood-derived cancer biomarkers have many uses beyond early disease detection – they can help with formulating a diagnosis, providing insight into clinical outcomes, or predicting a patient’s response to a particular treatment. Also, cancer biomarkers aren’t restricted to proteins (like PSA); other cellular, genomic, transcriptomic and metabolomic biomarkers may be found in blood as well [1,2].

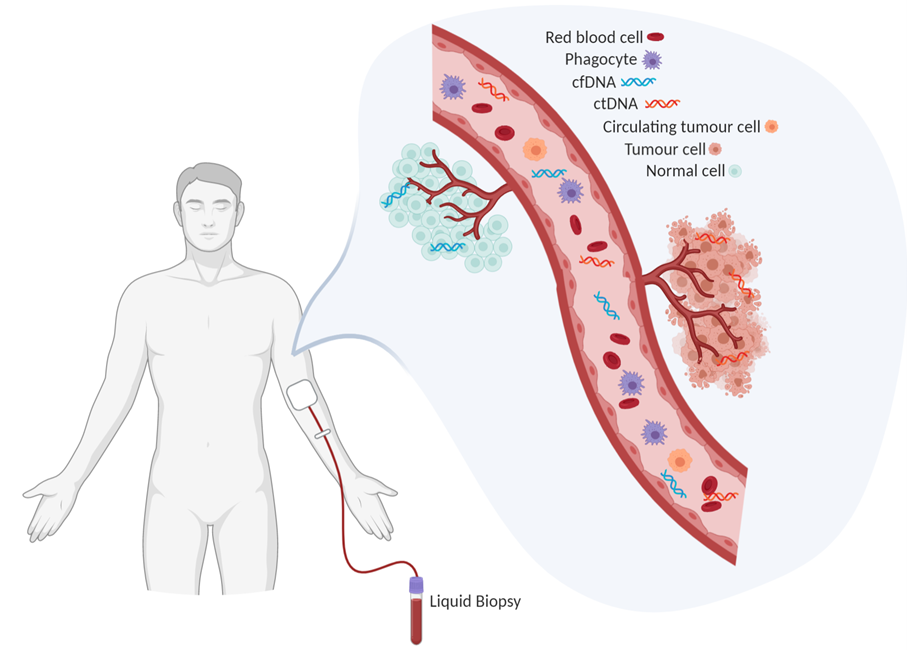

For this article, I’m going to narrow in on an exciting and relatively new cancer biomarker: circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA). When cells die, they release fragments of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) into the body’s circulatory system; when these fragments originate from cancer cells, they are called ctDNA. These fragments encode key information about the specific cancer, making them more favourable biomarkers compared to indirect approaches, such as PSA or radiographic images. The genetic mutations in ctDNA directly reflect mutations found in the tumour, which means that ctDNA can provide similar molecular profiling as a tissue biopsy [2,4]. That’s why blood tests to detect ctDNA are called liquid biopsies.

Figure 1. Blood contains a wealth of information about a person's health. Liquid biopsies can capture ctDNA circulating in a patient’s blood. Created in BioRender.

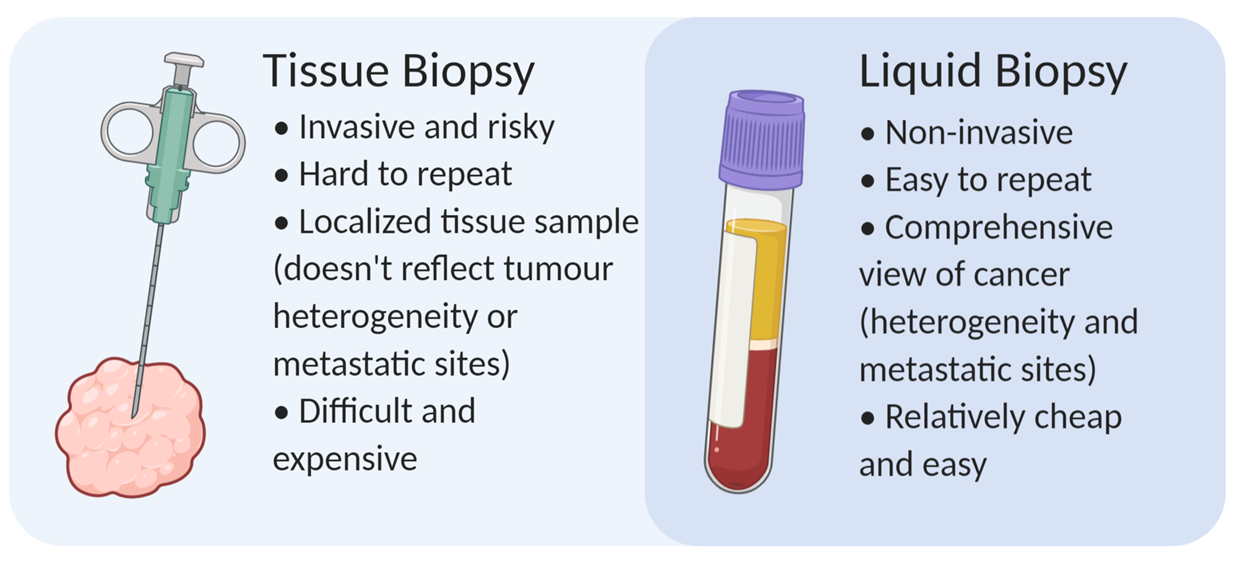

You may be thinking “If we can already get the same information from a tissue biopsy, what’s the point of doing liquid biopsies?”. However, liquid biopsies have some important benefits to keep in mind. The most obvious advantage is that liquid biopsies are easily obtained through non-invasive means [4]. For many cancer types, tissue biopsies can be difficult to obtain and a pain in the butt for patients (quite literally for prostate cancer, sorry dad). These invasive procedures also carry additional risks, such as postoperative infection. As a result, doctors are reluctant to repeat them, such as when monitoring treatment response. In contrast, liquid biopsies are easily obtained with a routine blood draw, which are less risky and cost far less. They can be easily repeated as needed for monitoring progression, drug response, and relapse [4].

Another benefit of liquid biopsies is that they provide a more comprehensive view of the disease. It is important to understand that tumours can be heterogeneous – in other words, different regions of the tumour might exhibit different characteristics because of their respective genetic mutations and local environment, to name a few contributing factors. Tumour heterogeneity remains an important challenge in treating cancers since the whole tumour might not respond to a given treatment uniformly well [5]. Heterogeneity poses an issue for tissue biopsies, since typically only a small portion of the tumour is sampled. Consequently, a tissue biopsy might fail to reflect heterogeneity within the tumour [4]. This was initially the case with my father’s prostate cancer. When he was diagnosed, they could not explain the rapid PSA increase compared to the low Gleason score of his prostate biopsies. A subsequent MRI revealed some cancer cells lying outside the normal sampling areas. As a result, another biopsy was conducted in this area, revealing a much more aggressive and fast-growing cancer. With liquid biopsies, most cells from the tumour contribute to the cfDNA pool, so a liquid biopsy should reflect the full diversity of the cancer [4].

Building on this concept, liquid biopsies may encompass ctDNA from metastatic sites as well, typically well before the metastases are apparent through imaging. Liquid biopsies provide insight into spatial and temporal tumour heterogeneity at multiple sites throughout the body [2,4]. My father had his prostate removed, leaving behind nothing to biopsy; however, a liquid biopsy can monitor whether the cancer had metastasized prior to the prostatectomy (hopefully not). This particularly emphasizes why liquid biopsies are a valuable tool, even in cancers where it’s easy to take a tissue biopsy (like breast cancer).

Figure 2. Liquid biopsies carry many advantages that make them an attractive compared to standard tissue biopsies. Created in BioRender.

It may sound like liquid biopsies are pure gold, but there are caveats. One main challenge is detection sensitivity when there’s low amounts of ctDNA in the blood [2,4]. The amount of ctDNA varies depending on tumor size, vascularity, other anatomical features, and the patient’s history of treatments (if they’ve had any) [4]. So depending on the clinical setting, particularly in cancer screening or relapse detection, there may be low amounts of ctDNA. Fortunately, continual development of various PCR and next-generation sequencing techniques are improving the sensitivity of ctDNA detection [2,4].

All in all, tumour tissue biopsies won’t be disappearing anytime soon, but liquid biopsies are an exciting area for growth. There are many clinical settings where they could be applicable, such as cancer screening, therapy selection, monitoring treatment response, or monitoring recurrence [2,4]. Commercial companies see this value, and tons of money have been invested into developing technologies for ctDNA testing, some of which are in the clinic already. I hope you can see the value as well, and that you enjoyed reading this simple introduction to liquid biopsies and ctDNA. If you still have reservations about liquid biopsies, just think – which would you prefer: a blood test or getting a hunk of tissue taken out of you?