When it comes to applying electrodynamics to advance our understanding of physiology, the brain ranks among the most common applications. This doesn’t come as much of a surprise; the brain is a dense collection of neurons which fire electrical signals (action potentials) to communicate with other downstream neurons or tissues. The regulation of the volume and rhythm of firing is responsible for how we move, how we speak, and how we breathe. The dysfunction of firing, occurring through various mechanisms, is the cause of many neurological disorders, especially those defined by motion and sensory abnormalities. Take for example multiple sclerosis, a disorder characterized by the loss of myelin around neurons in the central nervous system, resulting in weakened neuronal activity and motor dysfunction [1]. Clearly, the regulated firing in populations of neurons can be viewed as a potential end-goal in clinical neuroscience, but how do we go about arriving at this desired outcome?

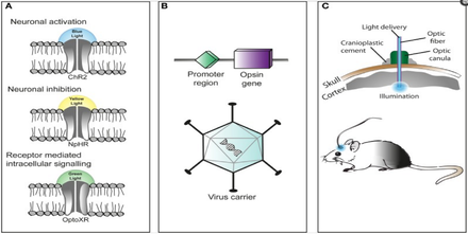

There have been a variety of proposed methods throughout the years, including electrical stimulation of neuronal populations and pharmaceutical control. One method which has recently received a lot of coverage is optogenetics. While the name itself might be off-putting and distressing, I can assure you that the general mechanism is quite straight forward. Optogenetics is a way to control neuronal activity through the use of light and genetic engineering [2]. Now, how can light possibly control the activity of the brain? First, remember that the brain is composed of populations of neurons; many of these populations are unique from one another in that they express different proteins. Also take note that neurons communicate with each other by releasing neurotransmitters which bind to the receptors of downstream neurons. These neurons then respond by opening neuronal channels, allowing for either an inhibitory ion influx (ions which result in cell inhibition) or an excitatory influx (ions which result in cell excitation), depending on which type of neuronal channel is present. Receptors and channels come in a variety of forms, responsive to a wide array of ligands; it turns out that there are receptors, known as opsins, that are responsive to light [2]. Some examples of these receptors, along with the wavelength of light which controls them, are shown in section A of the figure below.

While the brain doesn’t have receptors/channels which can ‘see’ and respond to light, that doesn’t mean they can’t be introduced to specific neuronal populations of the brain. With the advent of genetic engineering, there have been numerous methods proposed to deliver particular genes of interest to specific cellular populations; the general mechanism is seen in section B of the figure above [2]. Essentially, a viral vector can be used to deliver a particular gene (one that encodes an opsin) to a targeted neuronal group, which is denoted by its associated promoter sequence. Once delivered, light of the correct activation wavelength can be directed to a particular brain region of interest, containing the targeted neuronal population. Depending on the type of opsin gene introduced into a given cell type, we can either stimulate or inhibit neuronal activity. What I’ll introduce next is a vast oversimplification, but it gets to the heart of how optogenetics works in a particular scenario. Let’s say we want to stimulate a group of dopaminergic neurons in the brain. We can deliver an opsin – say, one that stimulates neuronal activity (such as ChR2) – attached to an upstream promoter specific for dopaminergic neurons (such as Drd1) into a mouse model. Then, depending on the region of interest, we can stereotactically introduce a light diode or probe. From there, we can specifically turn on or off the targeted neurons with the flick of a switch!

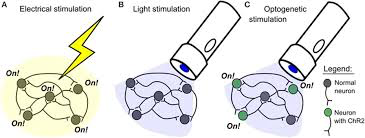

Where do methods such as electrical or pharmacological control stand in comparison to optogenetics? While optogenetics is not without its pitfalls, it is spatially and temporally superior to the pharmacological and electrical methods [3]. Its comparison to electrical stimulation is delineated in the figure above [3]. As shown, electrical stimulation is spatially imprecise, activating all neurons in a given target area. In contrast, optogenetic stimulation will only target the neurons encoding a particular opsin channel. With regard to pharmacological control, optogenetics is temporally superior as stimulation/inhibition can be modulated with the flick of a switch, whereas pharmaceuticals are inherently slower to take effect and persist longer than intended [4].

Throughout this read, I hope that you have developed an understanding of how optogenetics works and its potential applications. I also hope that you’ve garnered some excitement about this topic. While there are many factors which still need to be addressed in the full optimization of optogenetics, it has proven itself to be a very promising technique and shows great potential for further applications. If you are interested in reading about a particular application of optogenetics in depression research, take a look at this padlet that I worked on with a group of students last year!